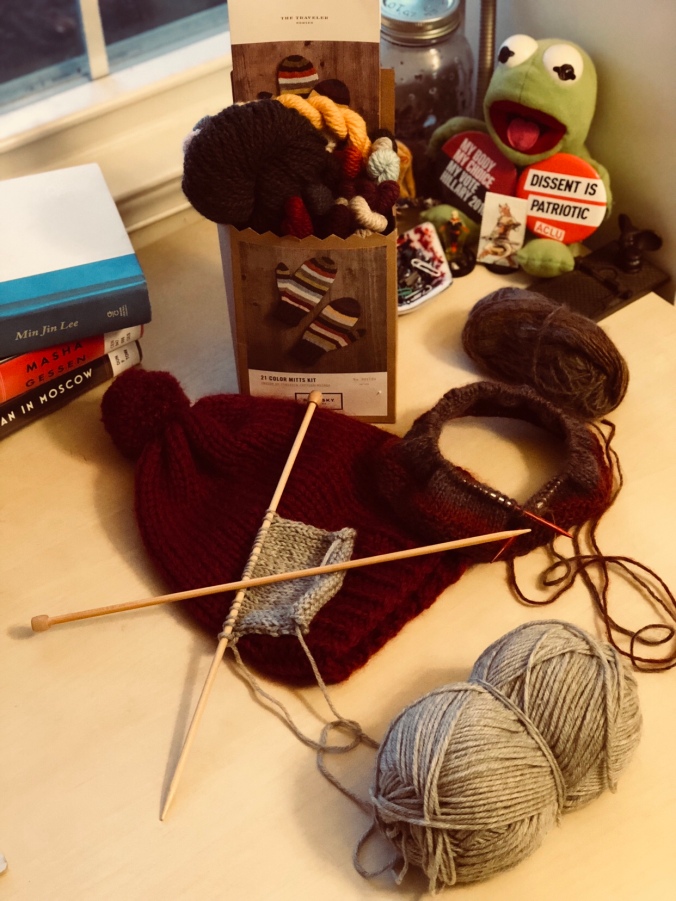

This is easily the most knitting I’ve done in years and I’ve only actually finished one thing

I think everyone wants to make something. I don’t believe there is anyone who wants to go through life without leaving any trace of having lived it.

When I was little, my father worked mostly out of the garage attached to our house. He built bits of cabinetry to install in other houses. He built our next door neighbors’ bookshelves and their deck. He built our bookshelves and our deck too. I’m pretty sure he also built our garage, but I don’t think I was alive for that. Sometimes, we’d sneak out to watch him work and he’d hand us a hammer, spare nails, and wood and we’d construct rickety tables for our stuffed animals or he’d give us wood glue and direct us to a pile of sticks. It occupied our hands so he could work. He came in the house at night smelling like work— sweat and cut lumber— and complain (not seriously) that we didn’t wait until he was cleaned up to start climbing on him. Later, when he started working on sales floors and then in offices and dressed like everyone else’s dad for work, he’d still spend weekend afternoons in his shop. Biking home from the pool or a friend’s house, you could hear he was outside before you could see— the sound of a table saw and Bach drifting over the top of the hill.

The outside of the garage doesn’t look the like it did when I was little. My parents covered it in siding and swapped the hinged doors held shut with a tree stump for a red garage door you need to have a code to open. It’s safer, but it looks like everyone else’s garage in the neighborhood now. You can still find my dad out there sometimes. I don’t think my father can go for too long without making something with his own hands.

I come from a line of people like that—machinists, sign-painters, farmers, and carpenters— people who tinkered and crafted and could point to a physical object and say, “I made that.”

Maybe that’s why I started taking a knitting class a couple weeks ago— I’ve gone too long without making anything but toast. My boyfriend is the one making our bread. I just burn it an acceptable amount. Maybe I needed to remember what it’s like to watch something come together, stitch after stitch, row after row, into an thing I can hold in my hands. The shape of the thing isn’t immediately apparent. It takes a couple inches before any pattern really emerges. It can take a couple inches before you realize you’ve made a mistake and need to go back. You might lose a half hour and a hundred stitches. You might, like I’ve done more than once in the last two weeks, have to pull out every stitch and start again. This is where knitting is preferable to woodwork. The mistakes are less expensive to fix. Even cut, yarn is more forgiving.

Over the last two weeks, I’ve also re-learned a skill I thought my hands had forgotten. This isn’t entirely new to me. A friend taught me how to knit in high school. We sat outside a pizza shop and she walked me through a simple cast-on and the knit stitch. I think I spent a couple months making a scarf that was a little more curved than a rectangle is, traditionally. I picked up needles and yarn every couple years after that but only finished one or two projects. I’d get frustrated reading patterns and trying to follow poorly-shot online tutorials. In the last weeks, I’ve only finished one project — a simple hat that didn’t need any increases or decreases and only required me to whisper “knit, purl” to myself for few rows before switching to knit all the way around. But right now, there is a physical object in my drawer, alongside hats and scarves I’ve bought, that I can point to and say, “I made that.” I’ve started another hat and will start a scarf tomorrow in class. I’ve bought a kit to make a pair of striped mittens and am talking myself into attempting what looks like a relatively simple sweater if I’ve read the pattern right. I’m not there yet but, with practice, I could be.

Knitting is a quiet, repetitive exercise I can do that makes sense. Mistakes are fixable. Imperfection is inevitable. Nothing handmade is without flaw. But there, in that sometimes stumbling repetition, is a quiet prayer to order out of chaos. You form a thing— a scarf, a hat, a sweater, a blanket— from a pile of string. You form it out of knots. We are forever untangling shoe strings and drawstrings and the cords attached to our earphones but here, you can make a beautiful mess of something to give it a unified meaning. You can give those knots shape and meaning in a world that feels sometimes formless and without meaning. When you are done you have something— a scarf, a hat, a sweater, a blanket— to guard you against that same world. You make your own shield.